Yesterday Vancouver City Council approved the third phase of the Cambie Corridor plan, which will guide future growth along the Canada Line, the LRT line completed for the 2010 Winter Olympics. While Vancouver had always intended to preserve affordable housing along the corridor and use community amenity contributions to support new affordable units, the approved plan is a truly well-balanced attempt at increasing density in a existing neighbourhoods while protecting affordability and equity. There are a lot of lessons here for other municipalities attempting TOD, protection of affordable housing or creation of new rental housing, all of which have proven difficult for Canadian municipalities.

Yesterday Vancouver City Council approved the third phase of the Cambie Corridor plan, which will guide future growth along the Canada Line, the LRT line completed for the 2010 Winter Olympics. While Vancouver had always intended to preserve affordable housing along the corridor and use community amenity contributions to support new affordable units, the approved plan is a truly well-balanced attempt at increasing density in a existing neighbourhoods while protecting affordability and equity. There are a lot of lessons here for other municipalities attempting TOD, protection of affordable housing or creation of new rental housing, all of which have proven difficult for Canadian municipalities.

What Vancouver has done in its typical, well-structured and clearly documented way is address the fact that gentrification will definitely occur in this corridor. Council was under pressure to address affordability concerns as several high-end developments were already underway–and well they should be. It’s been nine years since the Canada Line opened and everyone knew land prices would soar immediately as it always does with new LRT infrastructure. At the time, there was a lot of underused land along the corridor (click here for photos from 2009) and despite Vancouver’s attempt to preserve industrial land, it was well known that some of this land would be gobbled up by developers seeking to build luxury high-rise condos, the city’s stock in trade. Not only does Vancouver’s phase three plan address affordable housing, but it goes beyond that with its Public Benefits Strategy which acknowledges the need for new social amenities, recreational facilities, and employment in the corridor. Clearly the 60 public events and extensive online consultation contributed to the development of the plan.

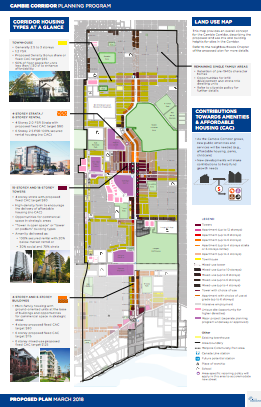

The population in the Cambie Corridor will more than double from 33,600 in 2011, as 45,700 new residents will be living in the area by 2041. The plan sets targets of building 5,000 secured rental units, 2,800 social housing units, and 400 below-market rental units targeted to those earning between $30,000 and $80,000. More than 1,700 existing single-family housing lots will be used for these projects. This means that fully one-quarter of the anticipated 42,000 new residential units will be affordable.

There’s a level of detail in the plan that is lacking in many others: on p43, in the area of Heather and 16th, the City describes the mixed-use 4-5 storey development or 100% secured rental housing they would like to see and state that, “On existing purpose-built rental housing sites (750 16th Avenue, 711 17th Avenue, 3217 and 3255 Heather Street), existing tenants will be entitled to compensation and assistance in accordance with the City’s Tenant Relocation and Protection Policy and its guidelines.” On p56, the exact lots that would be consolidated for a 100% secured rental project are listed; p67 outlines the exact square footage of non-profit organization space, space for a youth centre, childcare facilities, and artist studios that would be required for sites between 39th and 45th Avenue. A closer look at the plan reveals a generally mid-rise approach to density along Cambie, with a concentration of 15- to 18-storey towers near Cambie and 41st. There are some special sites for redevelopment, like the YMCA site near Langara College which will be targeted for 80% condo/20% social housing or 100% rental with 20% below-market rental; Balfour Block at the north end of the corridor will include replacing existing and maximizing new rental units, with a target of 25% below-market and childcare on site. The plan constantly refers to the City’s other plans and strategies, indicating how it reinforces the City’s priorities and goals (e.g. on p27 it explains how the Cambie Corridor Plan helps achieve the goals of Vancouver’s 2017 Housing Strategy).

Elements of the plan’s Public Benefits Strategy include include more than 20 acres of parks, childcare centres (1,080 new spaces), community facilities (civic centre and seniors centre), and improvements to the public realm. Through collaboration with the Oakridge Municipal Town Centre, the plan hopes to attract 9,200 new jobs to the corridor. Transportation improvements will include a #41 B-Line (finally!), and improved capacity on the Canada Line, upgrades to the cycling network.

Expect these targets to be carefully monitored and documented online, something the City has done with most of its other plans. This makes it easy to determine its success at key time points (e.g. ten years after implementation). Vancouver is excellent at documenting its plans and strategies: the Cambie Corridor page on their website even allows you to “read the plan in various levels of detail”: two minutes (infographic), ten minutes (plan summary), twenty minutes (consultation display boards), or the full plan.

While the City can’t solve all of its affordable housing or social problems, the Cambie Corridor Plan is light years ahead of the Halifax CentrePlan’s proposed corridor approach, which is currently available for public review. Corridor planning can be difficult when it includes high-order transit, which has been linked to gentrification. There is a temptation to focus on density and form above all else. The CentrePlan is a comprehensive plan for the entire downtown of the region, and as such it can’t get into the level of detail of the Cambie Corridor Plan. But there are some fundamental problems. First, the plan needs to outline the ways in which it reinforces the goals of other plans and strategies, something it misses the mark on. For example, the designated corridors do not align perfectly with the transit corridors outlined in the 2017 Integrated Mobility Plan. This will be critical if HRM wants to achieve a shift in transportation patterns and choices (Halifax actually saw an increase in its driving mode share from 2011-2016). Second, more specificity for the corridors is necessary to prevent massive redevelopment without regard to its social effects. HRM knows that gentrification will occur, but does not currently have an approach to slowing its effects, including protecting demolition of existing rental housing or ensuring replacement of units that would be lost in new development. The social and community elements of the plan are largely lacking, as is the attention to detail. In addition to this, all corridors are treated the same–vulnerable neighbourhoods like Gottingen Street, the historic black business area which still boasts lots of local shops, affordable rental housing, and social housing are treated the same as Young Street, which doesn’t have the same social concerns, demographics, or types of units. For example, a detailed corridor study for the more vulnerable Gottingen (a much shorter corridor than Cambie) could provide the same level of detail as the Cambie Corridor Plan and provide more clarity for residents and developers.

There is no such thing as a perfect plan, and Vancouver’s skyrocketing housing prices are proof that even when there is success, there may be harmful effects on affordability. But the Cambie Corridor plan is a rare attempt to plan for an entire linear neighbourhood in a much more comprehensive way than most cities in Canada have attempted. It is similar to the corridor planning approach used in cities like Tokyo, which has excelled in this area for decades and achieved a very high level of transit use. But it actually attempts to preserve affordability, consider social amenities and the improve the overall quality of life for residents. Let’s hope that it’s successful; undoubtedly, we will find out through future monitoring and evaluation of the plan.