Yesterday’s federal budget announced several new items to improve the affordable housing crisis in Canada, while spending less than predicted on health care and national defense. Currently about 200,000 new homes are built every year, and the government aims to double that to 400,000 in the next five years.

- a Tax-Free First Home Savings Account that will allow people to contribute up to $8,000 a year to a TFSA and withdraw it later to use for the purchase of their first home (with a lifetime limit of $40,000)

- a proposed two-year ban on the purchase of residential properties by foreign investors/buyers/companies who are not citizens or permanent residents of Canada (except recreational properties)

- a pledge to enforce the existing tax on anyone buying and selling a property within one year

- $4 billion for a CMHC Housing Accelerator Fund to create up to 100,000 units

- a reallocation of $1.5 billion in funding and loans to housing co-operatives and a commitment to work with the Co-operative Housing Federation and the co-operative sector, in developing the program

- $1.5 billion for new affordable housing units (on top of previous promises)

- $3 billion for repairs to existing units

- A tax rebate of up to $7,500 to encourage homeowners to develop a secondary suite for a senior or person with a disability

- A one-time increase to the Canada Housing Benefit for eligible renters paying over 30% of their income towards rent (administered through the provincial/territorial governments)

- $4 billion for Indigenous housing and $300 million over five years to launch an Urban, Rural, and Northern Indigenous Housing Strategy

Could this announcement be related to the National Housing Strategy?

While somewhat surprising, the budget announcement follows the publication of a report by the National Research Council Working Group on Improving the National Housing Strategy (Analysis of Affordable Housing Supply Created by Unilateral National Housing Strategy Programs, February 2022). Focusing on the Rental Construction Financing Initiative (RCF), the National Housing Co-Investment Fund (NHCF), and the Rapid Housing Initiative (RHI) (which together make up over half of the topline commitment under the NHS and most of the funding for increasing rental supply), the report found that very little housing (just 3% of RCF projects) has been built for low-income households, none were designed to meet the needs of people experiencing homelessness, and the RCF often accepts units with rents well above market rates. Just 4% RCF units could lift lone parents out of core housing need. While about 35% of units built through the NHCF are affordable to low-income households, just half of its projects (49%) could lift the median households in their areas out of core housing need. The report noted that the weight of the RCF program in the NHS portfolio seems out of step with the NHS commitment to addressing housing need, and that even if the RCF and NHCF were to produce deeply affordable units, the number of units produced would fall short of NHS targets. The RCF has dramatically increased the construction of purpose-built rental housing (which was 29% of all housing starts in 2019, just two years after the NHS was implemented), those units just aren’t affordable.

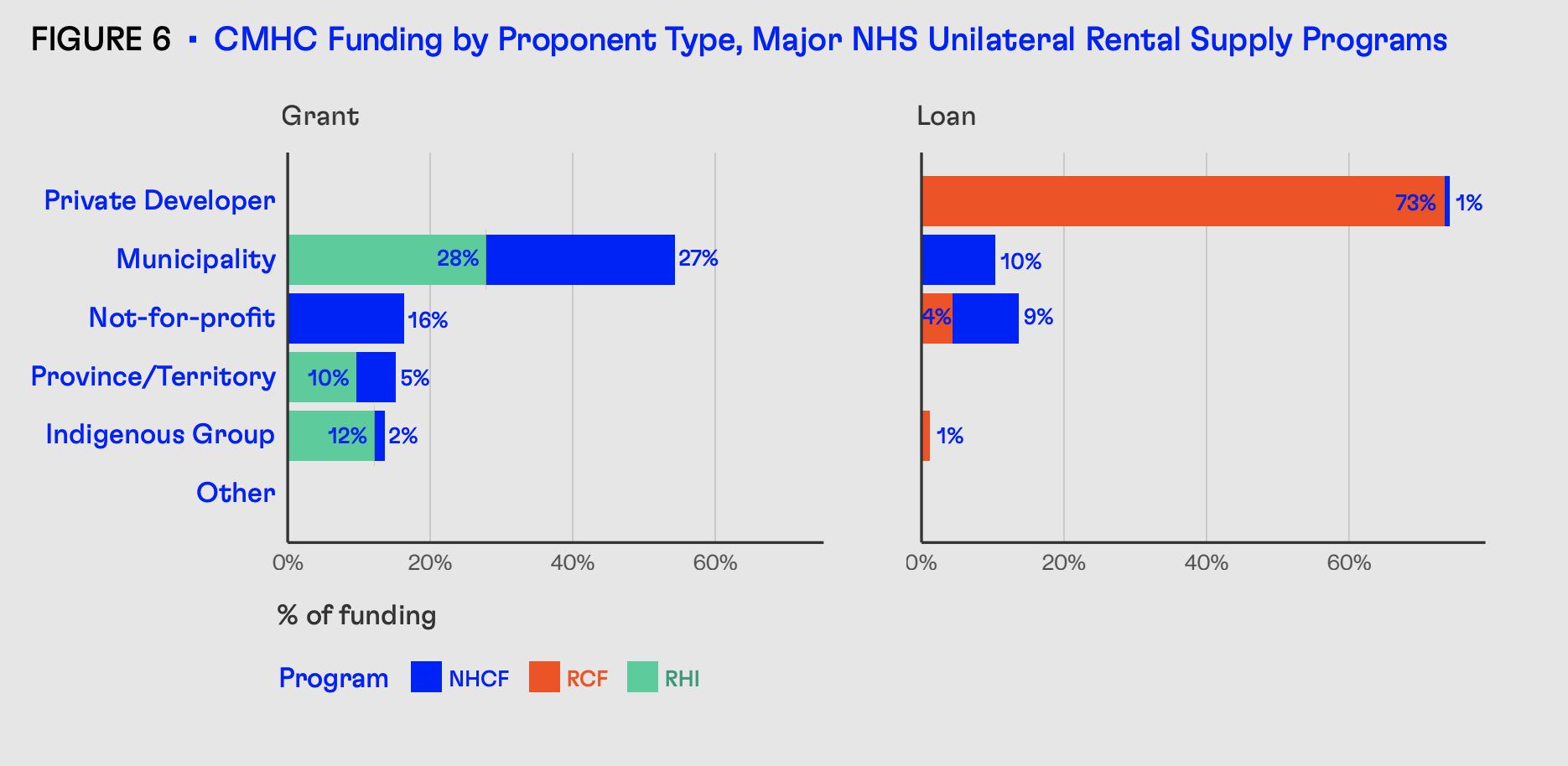

Considering that most Canadians in core housing need (66%) are renters, 80% of those in core housing need were in the bottom 20% of incomes, and 98% were in the bottom 40% of incomes, spending on deeply affordable rental housing does not meet the NHS goal of addressing housing need. Housing need is highest in the territories, followed by BC and Ontario (particularly Toronto and Vancouver, but also smaller cities like Belleville and Victoria). Quebec and the Atlantic provinces have the lowest levels of housing need. About $10.3 billion of the NHS funding has now been spent, with 75% of loans going to private developers and 55% of grants going to municipalities (almost half of which went to repair 60,000 Toronto Community Housing Units). Indigenous groups have received 14% of grant funding. Just 34,900 new rental units have been built, with over 60,700 repairs or renewals of existing rental units.

How is affordability calculated?

The analysis of the gaps goes deeper into affordability criteria for these programs. The RCF for example requires 20% of units to be affordable using the area median income in the area where the project is being built. However, whose income? Those of Census families (households led by married or common-law couples or lone parents), not those of singles or other household types. The report notes that the median income for a Census family is $90,390 before tax, compared to just $31,150 for non-Census family households. Affordability is also considered the same regardless of unit size: a studio apartment with a rent of $1750 would be considered affordable while a 3-bedroom home with a monthly rent of $2000 would not. Units funded by the RCF must remain affordable for at least 10 years.

The NHCF however, calculates affordability differently: at least 30% of units in NHCF-funded projects must be 80% of of the median market rent, which is calculated in relation to the size of the unit. But of course, many households could be in core housing need even if they were paying below-market rent. Median market rents are calculated at the Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) level, which means the rents in individual neighbourhoods could be quite different. Units funded by the NHCF must remain affordable for at least 20 years. Seven of the 10 projects with the lowest program-affordable rent to AMR were built by non-profit organizations.

The RHI defines affordability in relation to individual income, not household income, and RHI-funded units must not charge higher rents than 30% of the occupant’s income. RHI requires that rents must remain affordable for at least 20 years.

Discussion

The report concludes that:

- “any program intended to meaningfully reduce core housing need must create rental housing that would be affordable to low-income households” (p. 39)

- Housing need is deepest and most prevalent among those that have historically been marginalized and disadvantaged, and the National Housing Strategy Act requires the strategy to prioritize those in greatest need

- Supply created by the main NHS programs does not meet the needs of those in core housing need, and will likely not change the number of people in core housing need

- Appropriately designed criteria are required in program design to meet core housing need and allow the government to meet its targets

- Funding should be reallocated away from the RCF towards programs better suited to producing units affordable to low-income households

- Even if the RCF and NHCF were to produce more units, they still wouldn’t meet the targets in the NHS, so more funding should be put into bilateral programs and demand-side interventions like the Canada Housing Benefit

Given the fact that this report’s recommendations were to be shared with the federal housing minister a couple of months ago, the announcements under the federal budget make sense, particularly the reallocation of funding to build co-operative housing and the increase to the Canada Housing Benefit. Unfortunately for Nova Scotia, the fact that most housing need is in the territories, BC, and Ontario won’t help us secure more of the NHS program funding. The CMHC Housing Accelerator Fund will be carefully monitored to make sure units are affordable for the low-income. And why the focus on homeowners at all, considering just 33% are in core housing need? Because CMHC has focused primarily on growing homeownership since the 1980s, and they just can’t quit this habit because it generates them so much revenue: even in 2020 at the height of COVID-19, revenue from their mortgage insurance and mortgage funding was $3.0 billion. Almost a quarter of Canadians (23.2%) have mortgage insurance. The crown corporation will continue to develop programs that benefit homeowners even though they have higher incomes and more affordable housing costs than renters.

Chris Hall (CBC The House) interviewed me on this topic: listen to their April 16th podcast here.