A report published by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation (Berkeley) compares 144 state laws across the US that encourage or require municipal action on housing production. A collaboration with the Housing Crisis Research Collaborative, the report raises many of the same issues we’ve heard about housing supply in Canada: namely, that supply has been inadequate to meet demand, there are key barriers such as lack of labour and materials, and existing regulations on land use have had both positive and negative affects.

The 144 pro-housing laws reviewed by the authors illustrates the range of approaches states have used, including requiring local authorities to plan for the housing needs of their regions, implementing state standards for local land use and planning regulations, providing “carrots” for municipalities to incentivize a production goal, and imposing “sticks” to penalize jurisdictions for failing to meet their housing obligations. They focused on laws that required, permitted, or prohibited local action related to housing production–those that impact local planning and policy decisions–so municipal policies were not included. In about 30 states, they were unable to find any housing-promoting laws.

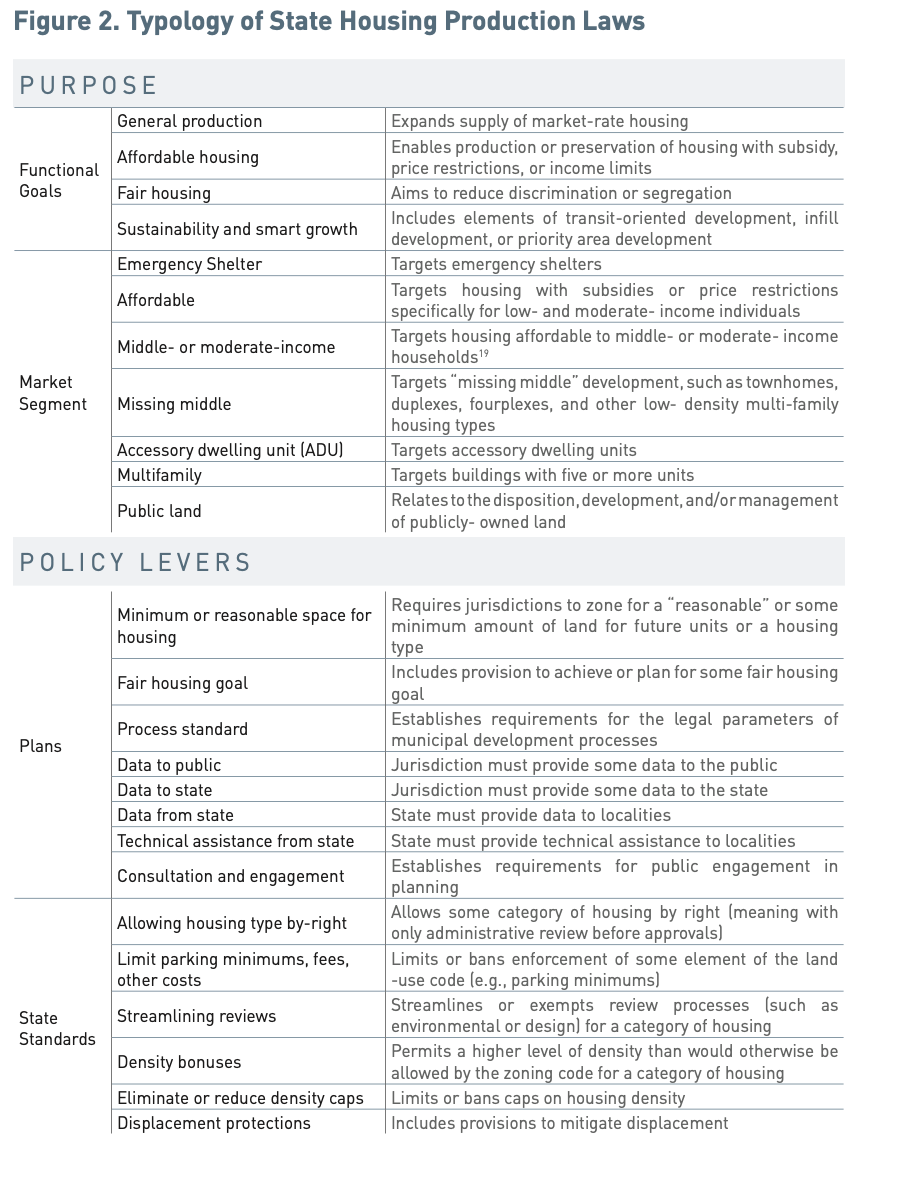

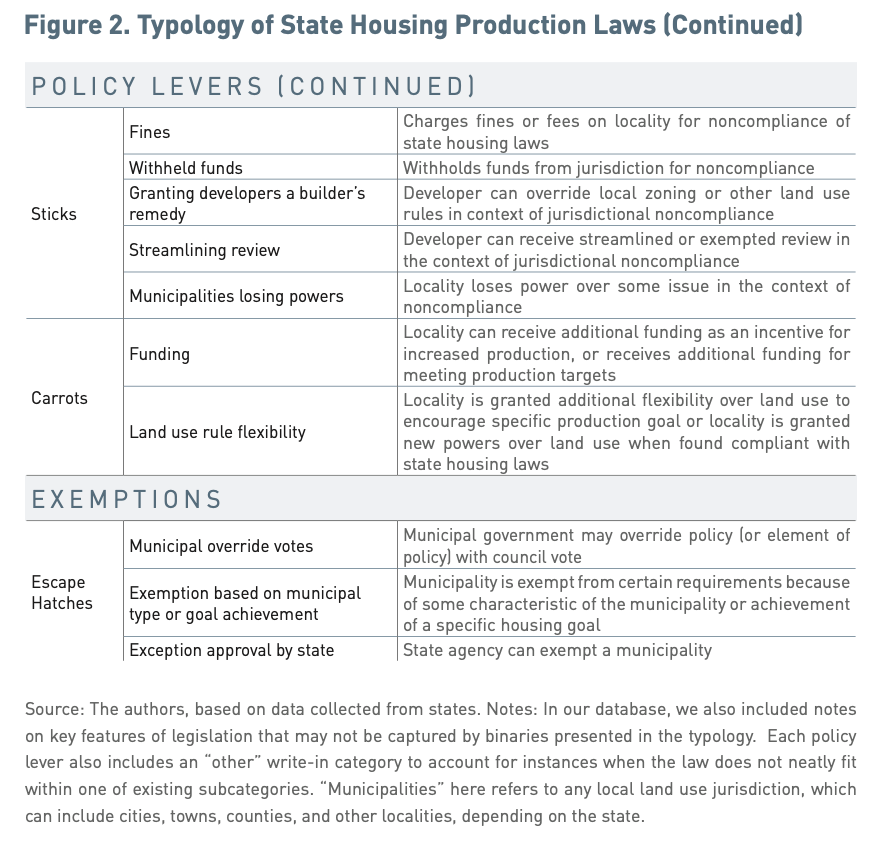

Using five regulatory concepts (plans, state standards, sticks, carrots, and escape hatches), they categorized the laws using an iterative process so they would be able to capture the breadth and complexity. In the end, they found three dimensions adequately characterized the laws: the functional goal and market segment (e.g. population it would serve, housing type), the policy lever (punishments for non-compliance, incentives for compliance, state standards that supercede local policies), and escape hatches (exemptions for certain jurisdictions for following the laws or certain conditions).

The authors found that laws often had multiple goals (e.g. increasing production of housing in general, increasing production/protection of affordable housing, furthering fair housing, or promoting sustainability), but most of the laws involved boosting the production of housing and/or affordable housing. About half of the laws had a “plan” component, such as requiring municipalities to plan for housing needs in their areas. “Sticks” or penalties for not fulfilling their housing obligations were the least commonly used component.

Some of the examples explained more thoroughly in the report are:

- Washington’s SB 5287 (2021) made changes to the Multi-Family Property Tax Exemption. The law already contained an exemption requiring 20% of units to be sold or rented to households with and 8-year exemption for which affordable housing is not mandatory. One new change is a 20-year property tax exemption to encourage affordable home ownership, which allows local authorities to offer a 20-year property tax exemption to qualifying projects as long as at least 25% of the units are sold to a government or non-profit housing provider that will guarantee permanent home ownership for households earning 80% of less of the Area Median Income. For projects with an existing exemption, the law offers a 12-year extension under the condition that 8-year projects convert to the 12-year program and adopt affordability requirements, and existing 12-year projects take on deeper affordability requirements moving forward. The bill also expands jurisdictional eligibility for the program to all cities.

- California’s Assembly Bill (AB) 2162 (2018) expands housing opportunities for people experiencing homelessness or are in need of housing with support services. It authorizes and streamlines local approval of affordable housing that includes a share of units for people who are eligible for housing with supports in zones where multifamily housing and mixed uses are allowed. Cities are required to grant ministerial approval of qualified projects with a minimum share of supportive housing in areas that already allow multifamily developments

- Maryland’s SB 273/HB 294 made updates to reflect new development patterns and trends, replacing the state’s 8 statutory visions, which drive state and local funding decisions and municipal plans, with 12 new ones. New visions include sustainability, priority growth areas, and community design, emphasizing compact, mixed-use, walkable growth in areas near existing or planned transit.

- Massachusetts’s Chapter 40R (2004) includes dense, mixed-use neighbourhoods with high affordability levels near transit or in areas of concentrated development. Communities can use state-authorized Smart Growth Zoning to allow projects by-right or with a limited plan review process. The law requires a minimum housing density in new zones established by the municipality. Using this overlay district will make cities eligible for Smart Growth Housing Trust Fund investments to incentivize denser developments.

- Utah’s SB 34 (2019) requires cities to show they are planning for moderate-income housing in their General Plan. They must demonstrate their planned residential and commercial development will meet projected needs for population and employment. If a local authority fails to plan for moderate-income housing near transit, the state may without funds from its transportation grants programs. There are zoning and funding incentives for moderate-income housing, and plans are required to be submitted to the state government.

The researchers found that state housing laws take many years to adopt, and are often improved through an iterative process if they aren’t having the desired effect. Jurisdictions should concentrate on implementation as much as passing the laws themselves, and the researchers say there is also likely more to be learned about the specific conditions, actors, and processes which led to adoption of the laws–for example, coalitions of local groups instrumental in building support for a proposed bill.

The research is interesting in light of the new $85 million federal program to help municipalities incentivize affordable housing by identifying and removing barriers. As Yonah Freemark argues for the Urban Institute, the program doesn’t ensure that higher-income neighbourhoods will accept new low-income housing–in fact, they’d be unlikely to apply because they don’t meet the criteria of having an acute need for housing affordable for people with incomes below the median in their area. A better option might be targeting funds to areas that currently have few subsidized units.