A more nightmarish city than Las Vegas cannot possibly be imagined by contemporary urban planners. That is a strong statement, but I stand by it.

The tacky neon signs and drive-in wedding chapels of yesteryear (still visible in downtown Vegas, where the Golden Nugget, the Four Queens and the Golden Gate are still open) seem quaint in comparison with The Strip today; in fact, many of the old signs are now part of the Neon Museum. Giant hotels line Las Vegas Boulevard, dwarfing the old standbys like the Flamingo, the Riviera, and the Sahara. Not that these three were any examples of planning or urban design. However, they had one main advantage: pedestrian-scaled facades and relatively low-rise towers. Their humble casinos, accessible with many glass doors at grade (and in the case of the Flamingo, slot machines right on the sidewalk), are shaded by ample awnings to protect pedestrians from the fierce desert sun.

There is a lot of visual interest for pedestrians (read: sensory overload) that is simply lacking in new monolithic structures such as the MGM Grand and the Wynn. Not to mention the more comfortable wind patterns created by the older hotels, which contrasts with the giant wind tunnel created by the new monoliths.

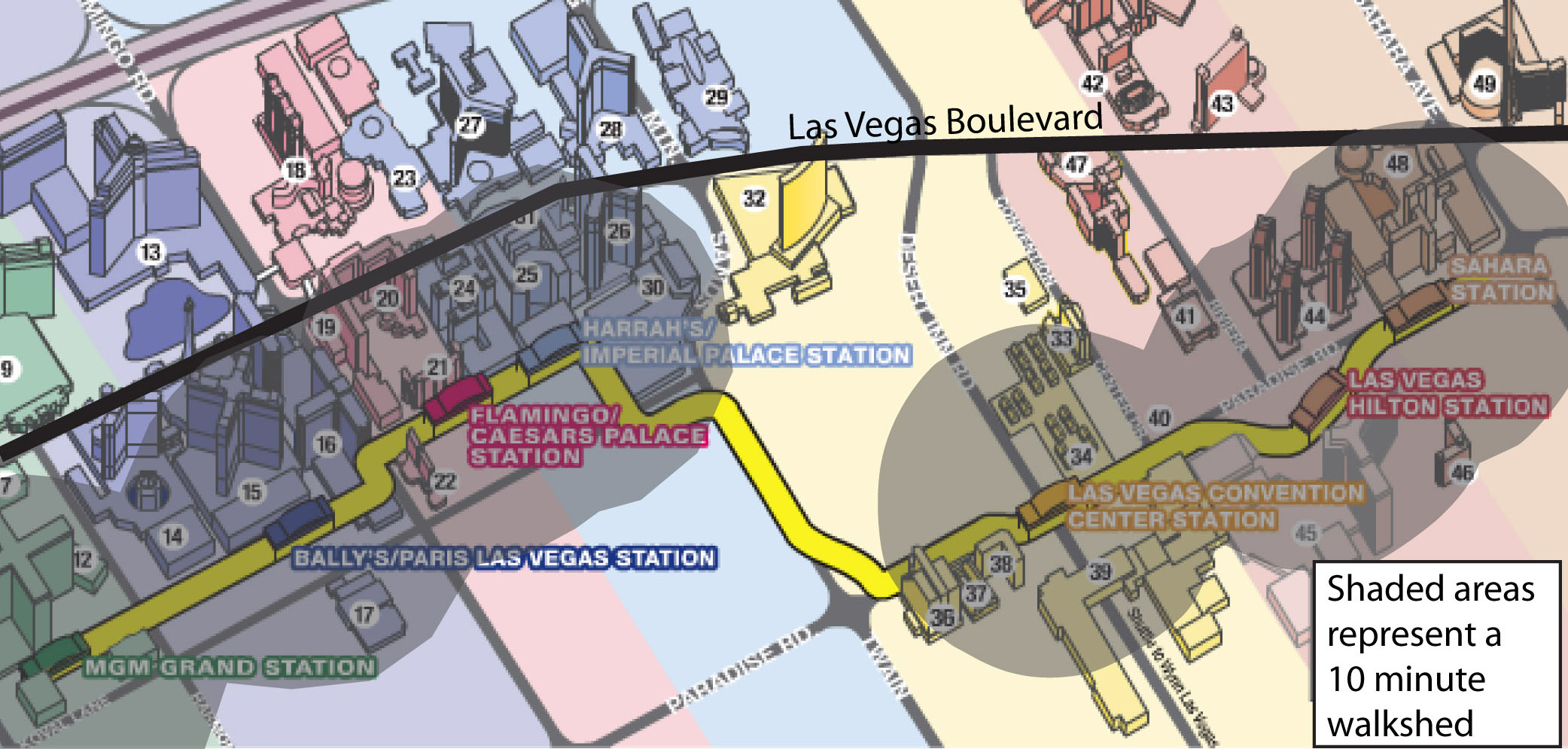

Getting around the city is a nightmare. Walking along The Strip is like doing an obstacles course: you’re constantly being forced into one mega-hotel or mega-mall after another, up pedestrian escalators and over bridges, since there is no consistent sidewalk area and traffic is maniacal. Despite this, thousands of people walk The Strip daily. You’d rather take a cab, you say? The lineup in front of the Bellagio on a weeknight is about 50 people. The bus? We saw at least that many people at a stop on a Friday night for the “Deuce”, the route that runs north along The Strip; at Fremont Street there were over a hundred waiting for the southbound bus. While its frequency seems admirable (it runs for 24 hours, every 8 minutes during the day and every 17 minutes from 2-5am), the bus stops at each block for ten minutes while each passenger laboriously feeds in three one-dollar bills and the stop announcements are likely to burst your eardrums. You still have the monorail.

But wait, to get to the stops you need to walk 10-15 minutes through smoky hotel casino lobbies, then ride the rail while listening to annoying tidbits and puns about Vegas, and then walk another 10-15 minutes to get back out to the street. And the last resort: driving. Good luck getting anywhere quickly, despite massive street widths of up to 12 lanes; the streets are jammed all day and all night. Your trip will likely take an hour regardless of transportation mode.

Those who study the impacts of grocery store location on public health would have a field day in Vegas. You cannot buy buy fresh fruits and vegetables, bread, or milk, anywhere near The Strip, nor is there a grocery store between The Strip and downtown. There are lots of restaurants in Vegas, and not a single deal outside of your local Denny’s or tacqueria. Hotel restaurants on The Strip are uniformly expensive, from the MGM’s Fiamma and Diego to the Bellagio’s Olives and and Fix, yet there are very few alternatives actually fronting onto the street. One wonders how these places will survive in an economic downturn; the McDonald’s, Starbucks, and Subway locations were all packed. Aggressive corporate interests have converted The Strip into a four-mile money trap.

Culturally, the city is rather polarized; perhaps a good indicator was the billboards advertising Barry Manilow and Tom Jones as well as little-known Danny Gans and Lance Burton. The city has a rather menacing gender mix: a glance around any casino in the evening will show you tables of men playing poker or shooting craps, while cocktail waitresses and the odd girlfriend or spouse are barely visible. Men dressed in brightly-coloured T-shirts offer you women on the street; one male friend walked the four-mile Strip and counted 60 offers. Surprisingly white (74%), Las Vegas has relatively small African American (12%), Hispanic (14.5%) and Asian (4%) populations.

All things considered, planners should use Las Vegas as a classic example of what not to do: obliteration of history, built form that is too grand for pedestrians to get around comfortably, few legitimate transportation options, poor mix of land uses, and nothing that would encourage social mix. The planning principles that govern our everyday towns and cities cannot, perhaps, apply to tourist towns, Vegas being the king of tourist towns. But as a tourist town, why not make it easy for tourists to get around the city? The answer lies in one simple truth: the new corporate casino. The design of these structures makes it nearly impossible to find exits, ensuring that tourists stay in the casino-lobby, enjoying free drinks and unlimited lost wages. Rather than focusing on the flashy outer shell of their buildings to attract gamblers, as the older casinos did, the new casinos excel at entrapment. This is the hint of misery that pervades Vegas.