As COVID-19 ravages the globe, we have an unusual opportunity to ask ourselves: how do cities function in emergencies? What services are considered essential? How do people, especially those in vulnerable communities, function in emergency situations? What can we learn from this crisis to rework our practices and routines?

Travel

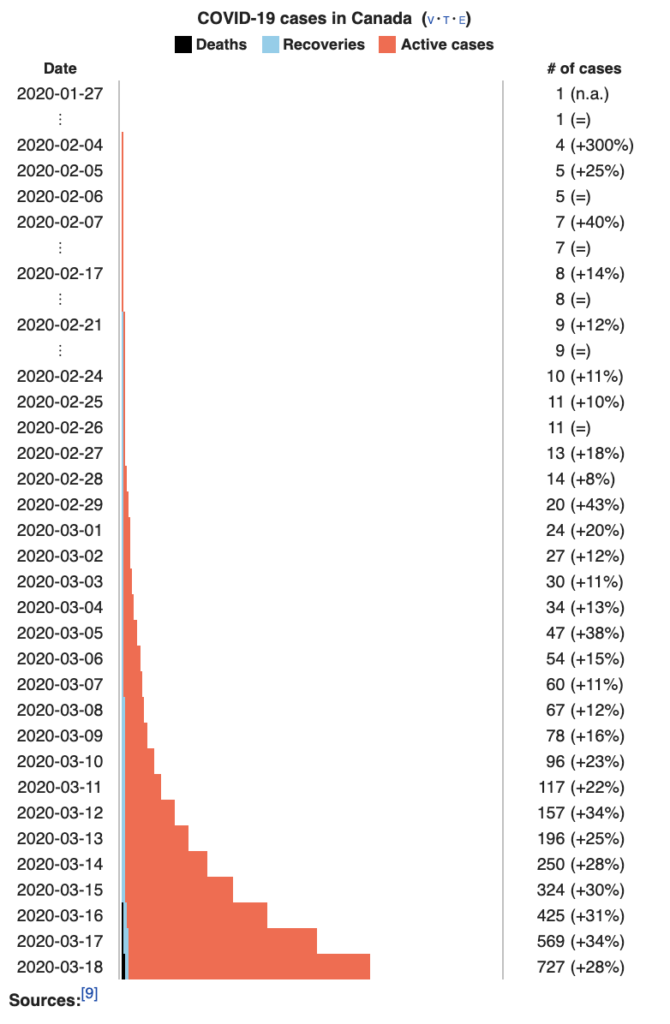

As of March 11, the date the outbreak was officially classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization, the Canadian government was advising against travel to the ten most affected countries, which at the tine included Italy, China, South Korea, and Iran (on this date Canada had 93 cases). Just two days later, we were being advised not to travel except for essential reasons and Canadians who are already abroad were being advised to return as soon as possible. On March 16, the government limited all international flights to just four airports: Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal, and Calgary and travellers returning from any destination were advised to self-isolate for 14 days. On March 18 (727 cases), for the first time in history, the Canada-US border was closed to all except essential goods being transported (e.g. food, medical supplies, and other essential trade).

This remarkable change in just a few days has had a major effect on our communities, limiting learning opportunities that are normally considered essential for planners: visiting and learning from other municipal/regional planners, presenting papers at conferences, and receiving feedback on our planning programs and research from experts in other countries. But it forces us to beg the question: how essential is all this travel anyway? Like climate protectors Greta Thunberg have been telling us, we don’t need to fly across the globe to communicate with others. Irish journalist Graham Docker commented that “COVID-19 has achieved in three short months what Greta Thunberg and her ilk could only dream of,” including a 25% decrease in emissions in China, 50% fewer planes in the sky over Europe compared to six months ago, and clear water in Venice’s canals. But such harsh travel restrictions, including closing borders throughout the EU, cannot last. Will we return to our usual means of travel once COVID-19 is no longer a threat?

As an academic researcher, I thrive on conferences to build and maintain my social and intellectual networks. Academia is an isolating place, whether you’re in your PhD or much further into your career as an associate or full professor. Connecting with researchers around the world has been necessary for my survival and intellectual development: for example, at the Association of European Schools of Planning conference in Gothenburg, Sweden in 2018, I reunited with an old friend and discovered we had several research interests in common. We were about to start fieldwork for a joint project in a few weeks in Malmö on transit-oriented development in the city. I’m not sure how researchers will adapt to decreased travel for fieldwork in the coming months–it could be 18 months before all travel restrictions are lifted and while it’s possible to switch to phone, Skype, or Zoom for interviews in some cases, there are lot of residents in low-income areas who do not have access to these or do not feel comfortable using them. Are we going to have to adopt distance research techniques in the future?

Public services

Just a few days after it was discovered that it was possible to transmit COVID-19 to residents who had not travelled to any of the affected countries (Canada’s first confirmed case of community transmission was March 5th), governments had taken swift action in first closing elementary and high schools, universities, and all non-essential public services including community centres and libraries. A few days later bars, restaurants, gyms, and virtually everything except grocery stores and pharmacies were ordered to close. Several provinces declared a state of emergency as well as several cities (e.g. Calgary). Public transit is still running in all cities, with restrictions such as requiring rear door boarding, cordoning off the seat closest to the driver, and switching to tap card payments for fares (or, in the cases of Saint John, NB and Halifax, NS, suspending fares altogether). Calgary was the first city to employ such measures, when the city declared a state of local emergency on March 17. What services are truly essential for communities, and how can governments ensure they keep running during a crisis of national or international magnitude? How do planners working for transit authorities, health authorities, and municipalities make these types of decisions? How are key workers such as bus drivers protected?

All the restrictions will have a huge impact for years to come–for example, public school students will miss months of education and parents will have to take time off to care for them. Without libraries or community centres, teens will have little to do, which historically has been dangerous. But with public gatherings of more than 10 people being banned in some communities, maybe little harm will come of this. Moving to online education, possible for universities with only a few weeks left in the semester, isn’t possible for public schools which rely on in-person classes and activities–but what will the long-term consequences be for universities and colleges, who have been pressured to hire fewer full-time, permanent instructors for decades? What does this mean for library funding in the future? For community programs and centres, so often the target of cutbacks?

Indigenous communities, particularly in rural areas where housing may be substandard, water quality low and general health conditions poor, are at particular risk. Fly-in communities have already begun to prohibit access by plane and the federal government has promised $100 million to help Indigenous communities which may be used for testing, providing rooms for people to self-isolate (which may not be possible within the community itself), and for additional medical equipment at the nearest hospitals. For years, the deplorable conditions in many of these communities has been a cause for concern, but things have been very slow to change. Will it take a pandemic to wake the rest of the country up to the badly-needed housing, health care, and education in northern and rural Indigenous communities?

Civil liberties

People have been warned against social gatherings of more than 50 individuals since March 11–in the US, the government is warning against gatherings of over 10 people for the next eight weeks. Residents of China and Italy balked at these restrictions at first, until they were enforced by the police. Malaysian armed forces are enforcing restrictions for people to stay inside after the country closed its borders. That hasn’t happened in Canada yet, but we could see increases in military or police presence in our communities if the Prime Minister invokes the Emergency Measures Act. The Emergency Measures Act allows the federal government much more power to provide safety and security during national emergencies, and has never been used. It was enacted in 1988 to replace the War Measures Act, which itself had only been used three times in Canadian history: WWI, WWII and the October Crisis of 1970. Two major changes ensure Parliamentary approval (the government has to prepare an explanation for the House and Senate on why the Act needs to be invoked), and that any temporary laws created under the Act are subject to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The repeal of the War Measures Act was critical because of its tendency to suspend regular civil liberties: it was used during the Second World War to require Japanese Canadians to register with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, restrict them from owning land or growing crops, detain them in internment camps, and force them to perform labour. During the October Crisis in 1970, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the Act ion response to actions by the Front de la libération de Québec (FLQ), who had kidnapped British diplomat James Cross and Deputy Premier Pierre Laporte (who was later murdered). Canadian military forces were deployed to assist the police in apprehending and arresting 497 people, in order to find FLQ members. Those arrested could be detained without cause for up to 7 days and were not allowed legal counsel. This is why the Emergency Measures Act that replaced the War Measures Act requires that all its resulting actions respect individuals’ rights and freedoms. If it is invoked, hopefully this requirement will prevent its being used against particular demographic groups or in any way except to prevent the community spread of COVID-19. The government has been urging, since February, that targeting of any community, or ethnic discrimination, is not acceptable.

Rachel Aiello at CTV News writes that travel anywhere within the country could be restricted under the Act, people could be evacuated from their homes, the distribution of goods and services could be regulated, emergency payments could be made to those who have suffered losses, and fines could be set for those who do not obey the rules set out in the Act or any temporary measure enacted under it. The Act would be in place for 90 days unless it is revoked by Parliament before that, but could be extended another 90 days if the situation hasn’t improved.

Social supports for workers

Thousands of workers in Canada do not have adequate sick days, especially those who are hourly or contract workers, work for or operate small businesses. With professionals such as dentists, massage therapists, restaurant servers, retail staff, and hairstylists unable to work, the Canadian government introduced a number of measures to ensure workers are protected for the time they are required to stay at home. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced $82 million in funding which is supposed to include:

- $27 billion for families (a temporary increase to the Child Benefit Plan, emergency care benefit of up to $900 per week for those that need to stay home and don’t have paid sick leave, an emergency support benefit for those who are now unemployed as a result of closures, increased GST rebates for low-income people, and other supports for people who are homeless, Indigenous, at risk of defaulting on their student loans, or are fleeing domestic violence)

- $55 billion to stabilize the economy (allow businesses to defer income tax payments interest-free until August 31, making additional funds available to businesses who need it to retain workers, and buying insured mortgage pools to stabilize funding to banks and lenders). Nothing yet has been said about assisting the airlines, who are in a worse position than post 9-11

If these types of supports are being introduced at a time of national emergency, why are workers falling through the cracks the rest of the time? Why is it acceptable for so many to have inadequate sick leave or benefits that would cover extended leave for health reasons? Why do most families struggle to pay for child care or other services they desperately need, if government funding could be accessed?

Just a quick look at travel restrictions, service provision, civil liberties, and social supports for workers shows how wide-ranging the effects of COVID-19 are on our communities. Planners working for municipalities, health authorities, transportation authorities, and many other areas are struggling to continue providing basic services for people while limiting the spread of the virus. Is COVID-19 exposing the cracks in our social support system? In the way we travel and learn? In our freedoms to congregate and travel? In the way health services are provided? Let’s hope so, and let’s hope we’re able to learn from these unprecedented times to build stronger communities for everyone.