New Toronto mayor Rob Ford has been making headlines: and not in a good way. Ford has long been a controversial figure, and this summer’s mayoralty race was no exception. Echoing Mel Lastman, a similarly polarizing figure, Ford seems an odd fit for such a multicultural, cosmopolitan, and diverse city. He’s at best a pompous blowhard with insights into the political process; at worst, depending on your information source, he’s a racist homophobe who doesn’t support affordable housing, public transit, or any of the other pressing needs of the burgeoning city. But like Lastman, who was in office for six years, Ford will likely have a lasting effect on the City of Toronto.

In Canada’s biggest city, where 22% of the population takes transit, Ford has decided that transit is the enemy. On December 1st, his first day in office, he managed to kill the city’s proposed vehicle registration tax, freeze property taxes, and get council’s approval to have the Toronto Transit Commission deemed an essential service. With this designation, the TTC will be unable to strike, and union leaders say they’ll fight the decision, which will be made by Ontario Premier Dalton McGuinty.

McGuinty and regional transit planning authority Metrolinx also have to deal with Ford’s tyrannical attack on Transit City, an initiative that was seven years in the making and is already being built. The province, after approving the construction of four LRT lines, announced this spring that they may not be able to fund the entire plan at this time. Ford wants to scrap Transit City entirely, arguing that streetcars cause traffic congestion, and everyone prefers subways anyway. He wants to extend the Sheppard subway line to meet up with the Scarborough RT instead, even if the high cost of this option means that no other transit infrastucture can be built in Toronto. Perhaps he isn’t aware that one of Transit City’s approved lines was a retrofit of the Scarborough RT, which is rapidly deteriorating, and another was a Sheppard LRT that would extend much farther than the subway will? In vain, Metrolinx tried to convince Ford that many other options were more suitable and affordable than subway extension, but surprisingly, the man who claims to be so concerned about taxpayers’ wallets wants the most expensive option. The main beneficiaries of Transit City were to be the inner suburbs: Etobicoke, Scarborough, North York. Neighbouring municipalities like Mississauga also strongly support Transit City. David Hulchanski, who just released an update to his popular “Three Cities within Toronto” study, says that building LRT is the answer to slowing or reversing the segregation of the city by income. Doesn’t Ford feel a responsibility to represent the suburban “working man” that elected him?

Electing Ford represents frustration: residents are frustrated with the way their city is run. Suburban residents see traffic congestion, unreliable public transit, job losses, and rising taxes, and they want things to change. What they don’t see is that municipalities are chronically underfunded by the provincial government in ways that matter: it is the provincial government that funds transit and road infrastructure, and a good proportion of job creation also comes from provincial initiatives. This underfunding leads the TTC to strike, since they rarely have the money for either their capital or operating costs, and also requires the city to raise money in other ways, usually new or increased taxes. Canadian cities have precious few mechanisms to generate money, and unfortunately taxes are among the few. The vehicle registration tax would have raised $64 million for the City of Toronto; Ford has not announced another way of raising the money. Opponents claim that it is “mathematically impossible” that these two tax losses won’t cause any service cuts for City residents. Cancelling Transit City could cost the province fees for broken contracts: $137 million has already been spent on Transit City and $1.3 billion is committed. In fact, for a pro-business, right-wing mayor, Ford doesn’t seem to be very good at managing money. Perhaps his 2011 budget review will inform him that transit actually makes money for the City of Toronto: former budget chief Shelley Carroll says that high transit ridership contributed to a year-end operating surplus.

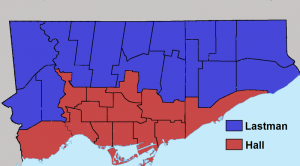

Both Lastman and Ford came into office at a time of economic recession. Both came to power after a period of progress for the City of Toronto: Barbara Hall (1994-1997) preceded Lastman and David Miller (2003-2010) preceded Ford. Both Lastman and Ford claimed to appeal to suburban “ordinary people”: indeed, the voting maps of Toronto illustrate the pervasive divide the media loves to play up (the Globe and Mail included). We know from US elections that the maps don’t tell all: as Joshua Kertzer and Jonathan Naymark wrote in the National Post,

“This attempt to create a downtown versus suburb cleavage is at best a distraction, and at worst, sets a dangerous precedent.”

Perhaps most tellingly, both Ford and Lastman faced a slew of opponents for mayor: Lastman was one of over thirty candidates, while Ford was one of 40. According to the City of Toronto’s website, 383,501 voters elected Ford: 813,984 actually voted in the election. So, 47% of voters, who represented 35.3% of the City of Toronto’s population, elected him: that’s 16.7% of the city’s population. Lastman, the first mayor elected after Toronto announced its amalgamation with five suburban municipalities, won by a slim margin of about 41,000 votes. In times of discord and recession, the appeal of the right-wing, cost-saving, businessman is strongest.

The next three years will be momentous ones in Canada’s biggest city. Ford will have to make allies in the provincial government if he wants to keep taxes low. Let’s hope that Ford has a fight on his hands, at least as far as transit is concerned: it takes very little to kill programs and policies that have taken years to approve. As Councillor Janet Davis said, “For the first time [we’re] expanding transit across the city that we waited generations for — the mayor can’t walk in on Day 1 and say, ‘it’s gone.’ It doesn’t work like that.” If anything, Ford’s rising star only proves how little power cities have over the issues that really matter to them, and how limited their sources of funding really are. The problem is that Ford’s blustery, and logic-free, decision-making will have long-term consequences on the City of Toronto: Lastman managed to have the Sheppard subway built, against the TTC’s advice. The result was a white elephant, no funding for additional services that the system badly needed, and at one point the streetcars running at very low speeds to cope with deteriorating tracks. While Vancouver is no stranger to provincial wrangling over transit infrastructure, at least we have a mayor who cycles to work and strongly supports sustainable transportation.