In my previous post, I wrote that many Canadians don’t know much about municipal planning processes, the implications of the legal division of powers in Canada, and what this means for service provision in our cities. In this vein, readers might be interested in some examples of municipal efforts at citizen engagement that go beyond the often-uninspired public meeting.

Participatory budgeting originated in Porto Alegre, Brazil in 1989. It’s driven by core principles such as democracy, equity, community, education, and transparency. Thousands of citizens assemble in Porto Alegre each year to elect delegates to represent each city district, prioritize demands, serve on the Municipal Council of the Budget, and produce a binding municipal budget. Proponents of participatory budgeting say that because people with the greatest needs play a larger role in the decision-making process, spending decisions tend to redistribute resources to communities in need. In Porto Alegre, for example, there has been a marked increase in funding for badly-needed sanitary sewer projects and schools. Participatory budgeting is used in about 140 municipalities in Brazil as well as towns and cities in France, Italy, Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom, India and Africa. It is used for municipal school, university, and public housing budgets.

The process has also been used in several Canadian municipalities: Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) allows its tenants to participate in decision-making on local, neighbourhood and city-wide spending priorities. TCHC’s participatory budgeting process first took place in 2001, when tenants were asked to help decide how to spend $9 million per year (13.5% of TCHC’s budget); 237 local capital projects were funded. In Guelph, residents allocate a small portion of the City’s budget through the Guelph Neighbourhood Support Coalition. Since 1999, neighbourhood groups have been sharing and redistributing resources for local community projects, including recreation programs, youth centres, and physical improvements to community facilities. In 2005 some 10,000 people participated in the process and 460 events and programs were funded.

In a review of participatory budgeting efforts in Canadian cities, Josh Lerner and Estair Van Wagner outline several challenges for participatory budgeting in Canada: the fact that Canadians are extremely diverse in language and culture, the small scale of these efforts so far, the limited power of citizens in the process, the fact that none of them have fundamentally changed their cities’ political systems or created a more progressive social agenda, and the potential for the process to become co-opted by politicians.

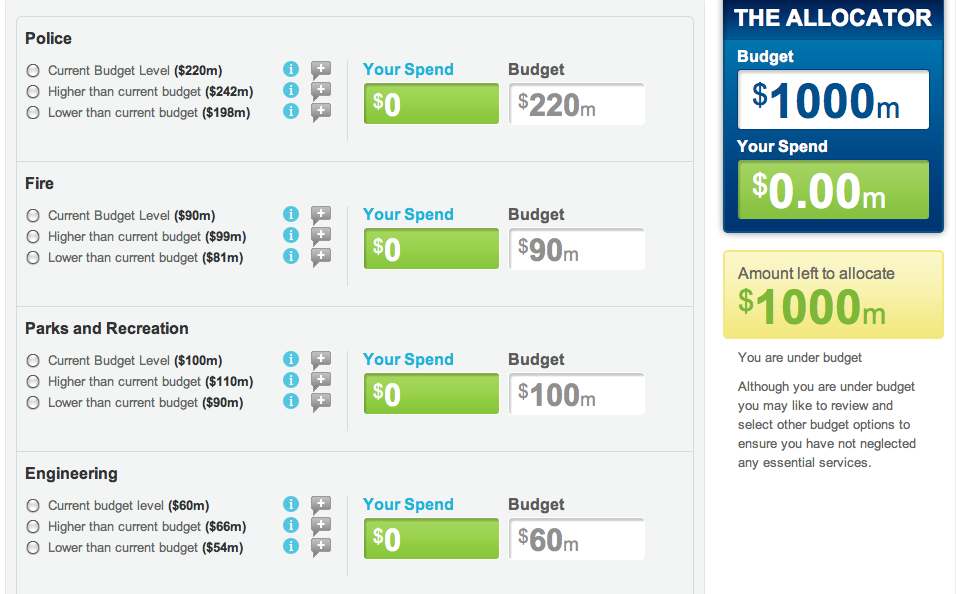

In February 2011, Calgary Mayor Naheed Nehshi opened up the budget planning process to the public through a citywide engagement process. In “Our City. Our Budget. Our Future.” the City aimed to help people feel like they were part of the process, make the budgetary process clearer by simplifying communication from city staff, and gather ideas on the budget. Their online budgeting tool allowed users to see how much each department currently spent, and what an increase or decrease in areas like transportation or safety would look like. The City heard from 24,000 people during this process. Again, citizens’ ideas were considered in drafting the budget, which was adopted in November 2011. The new three-year budget resulted in property tax rate increases of 6.0% in 2012, 5.7% in 2013 and 6.1% in 2014 and included (among other things) additional funding of $1 million for Calgary Transit, a reserve fund of $3.5 million for snow clearing in 2013 and 2014, a $225,000 increase to the Calgary Arts Development Authority.

“We used to do things like open houses and town halls when we had those discussions. And what we learned this time around is that the open houses and the town halls are the most expensive and least successful part of the process.”– Calgary Mayor Naheed Nenshi

The City of Vancouver followed suit this year, encouraging citizens to get involved in the 2012 budget process. In addition to attending public meetings and completing an online survey on budget priorities, a section of the City’s website lets users to download a primer explaining how the budget works (how the city raises funds, what percentage of taxes goes to pay for utilities, fire and police services, etc.). The interactive tool lets them “be Councillor for a day, see what it costs to run a city.” This simple tool gives you options to remain at the current level of funding or to increase or decrease funding levels in each area. When you’ve finished making your budget, the Budget Allocator tells you whether you have a surplus or a deficit, and how much you would have to raise taxes to cover the increased costs. You can submit your budget, along with the reasons for your choices, directly to city staff: if you’re a local, go to www.talkvancouver.com/Budget 2012 before February 10th to have your say.

In short, there are varying levels of participation in budget processes, from consultation to surveys to participatory budgeting. In addition to various levels of power for the participants, the educational aspects differ as well: one could argue that while Toronto, Calgary and Vancouver have made strides in educating the public on the budgetary process, they stop short of allowing residents to learn how to prioritize spending objectives and vote on them. Nevertheless, Canadians in other municipalities might want to find out how their budget works, when their budget is up for adoption and what the process is for citizen involvement. With so many online and interactive ways to get involved, there seem to be many opportunities to inform and involve communities that may not participate otherwise: young adults, immigrant groups, seniors living in facilities, etc. High school teachers, college and university professor could use the online budgeting tools in civics, planning, political science, or urban studies courses. Immigrant groups could organize online participation at a community event. Residents and health care support workers could help seniors participate. If your municipality doesn’t currently encourage participation in the city budget process, ask your councillor to suggest the idea.

Update: check out the latest national issue of Spacing magazine for integrated approaches to public engagement in Saskatoon, Vancouver, and Halifax (“Speaking with Your City” by Rachel Caroline Derrah).

Thanks for sharing this! The review article on PB in Canada that you shared was actually not written by Daniel Chavez and Einar Braathen. They were the editors for a book the article was to have appeared in. The article authors were Josh Lerner & Estair Van Wagner. For a pdf of the article see http://linesofflight.net/work/pb_in_canada.pdf

I’ve contacted TNI to have them fix this mistake on their website.

If people are more interested in this topic, they should also come to the first International Conference on Participatory Budgeting in the US and Canada, which will take place in New York City on March 30-31. See more info: http://pbconference.wordpress.com/

Thanks Josh. I’m sure you’ll draw a huge crowd for the conference, it’s an idea that should pick up momentum in North America.

Thanks for this post – it is a wonderful one about great opportunities to engage citizens in meaningful ways about a complex issue. Our firm designed, implemented and reported on the City of Calgary process and found it to be a thought-provoking and fascinating experience. We were astonished at the time, effort and energy so many participants took to provide their ideas, views and choices about City services and the budget that goes with them. It was a great experience and nice to see it mentioned by someone as worthy as reference. Thanks!

I wish PB was more visible. I find it quite difficult even as an academic that constantly seeks out journal articles and information on current practices to know when and where participatory practices in Canada are happening. Citizens just aren’t exposed enough, nor is media attention opening up to these sorts of deliberative practices, enough. At least this was the case with the type of expoure that the British Columbia and Ontario Citizens’ Assemblies recieved. Also, while nearly every government in Canada does in fact claim the to be ‘citizen friendly’ and more open, to what extent is there some form of transcendance from traditional consultation, to empowered participatory governance taking place? This remains understudied, though initial inclinations clearly point towards limited inclusion, agenda setting, and implementation powers. Much still needs to be done. Thanks for this post.