Like many cities in North America, Vancouver is in a love affair with roundabouts. And why not: traffic engineers tell us they improve vehicle safety, increase roadway capacity and efficiency, reduce vehicular delay and emissions, provide traffic-calming effects, and mark community gateways. But hang on…isn’t this just another road design that prioritizes cars over pedestrians and cyclits?

At a roundabout, pedestrians must wait until there is a gap in traffic to cross, placing them at a considerable disadvantage from traditional stop signs and stop lights. There is no designated time for pedestrians to cross, like a walk signal, which means at a busy intersection you can wait several minutes. And there are reasons to fear for pedestrian safety as well.

Studies shows that while the risk of serious vehicle collisions is decreased, this is mainly because they reduce collisions where cars run red lights/stop signs or drivers misjudge the gap in oncoming traffic while turning. The US Access Board, a Federal agency committed to accessible design, writes that “the research findings on pedestrian safety at roundabouts are less clear. There have been relatively few studies, mostly conducted in Europe, concerning pedestrians and roundabouts.” Little is known about the effects of roundabouts on the particular demographic groups, such as the elderly, children, and those with accessibility issues. Many drivers do not yield to pedestrians at crosswalks, and it might be difficult to tell if they plan to yield; as the traffic volume increases, the number of “crossable gaps” decreases.

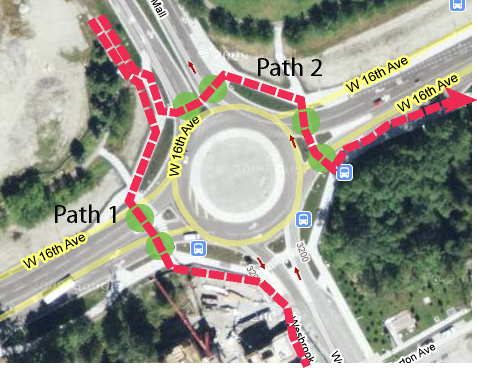

The design of a roundabout also pushes the crosswalks away from the intersection, creating travel paths that are inconvenient for pedestrians, according to the New Urban News. New Urbanists have been promoting roundabouts for many years as a traffic calming measure, despite any evidence that they increase pedestrian safety.

In England, where roundabouts are commonplace, drivers are reasonably vigilant and yield to pedestrians. Nevertheless, the real advantage of roundabouts is that cars are not required to stop. Drivers generally like them for this reason; it reduces their travel time. But what does this do for pedestrians? It again places them at the bottom of the pecking order, and places them at considerable risk. It also lengthens their travel time considerably, as they must cross several directions of traffic, waiting for gaps each time. Compare this to a regular four-way signalled intersection, where the pedestrian gets a clear walk signal and does not have to determine whether it is safe to cross. In other words, the problem that cars supposedly have at four-way intersections (trying to judge the gap in traffic) is transferred to the pedestrian, who is not encased in steel for protection.

Interestingly, public opinion on roundabouts is divided. Many drivers I know detest them, and find them difficult and confusing to use. A cab driver recently told me that he hated the new roundabouts in Vancouver, but one friend of mine defended them. She hails from England and says that the problem is simply public education: North American drivers just don’t know how to use roundabouts. When the issue of pedestrian safety is raised, she said, “I see nothing wrong with pedestrians having to wait a few minutes to cross the street. There’s way too much encouragement of pedestrians getting the right of way all the time, even when it’s unsafe.”

I wonder what experts like Barry Wellar, a retired University of Ottawa professor who studies public safety and testifies at trials where pedestrians and cyclists are injured, thinks about roundabouts. Wellar developed the Pedestrian Safety Index, which some municipalities have been using to evaluate their busiest intersections. Similarly, John Pucher of Rutgers University discusses the many innovations in Europe designed for pedestrian safety, including advanced crossings for pedestrians, scatter crossings, grade-separations and separate pedestrian and cyclist signals. One of Pucher’s main arguments is that pedestrians and cyclists increase in number with increased safety precautions; he also argues that penalties for striking a pedestrian or cyclist are much harsher in Europe.

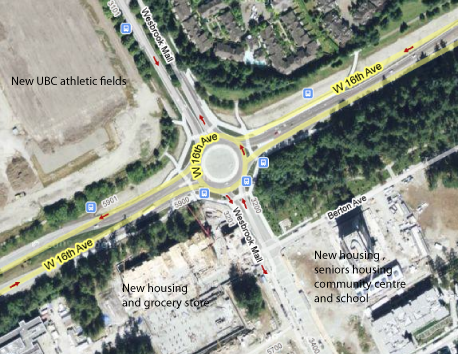

Surely we should be examining all the different safety aspects of roundabouts if they are to be applied everywhere from quiet residential streets to major intersections such as the one pictured in this article. My guess is the UBC roundabout, which was converted from a signalized intersection last year, will prove treacherous to the pedestrians (many of them seniors) crossing the intersection at 16th and Wesbook Mall to access the new grocery store, community centre, school, and housing in the area. But UBC already has plans for another roundabout, and like many municipalities seems content to let traffic engineers’ reports lead the way.

The US Access Board makes several suggestions for improving roundabouts for blind pedestrians, including:

- Landscaping, planters, pedestrian channelization, bollard-and-chain separation, railings, and other architectural features can delineate paths that lead to the crosswalk and prevent or discourage crossing at locations other than the crosswalk; a distinctive edge such as a raised curb

- Traffic calming measures to ensure vehicles are travelling at low speeds, which influences whether or not they will yield to a pedestrian

- Raised crossings to discourage vehicle acceleration

- ‘Smart’ signals that can sense and signal a pedestrian’s presence

- ‘Splitter’ islands with a detectable surface, which can be used as a pedestrian refuge

- Public awareness campaigns encouraging drivers to yield to pedestrians

These measures can help counterract some of the pedestrian safety issues associated with roundabouts, but the fundamental question of whether they are advantageous for all transportation modes is not addressed. Pedestrians and cyclists are considerably disadvantaged by roundabouts as compared to traditional street crossings, proving once again that traffic engineers have a tendency to prioritize cars’ needs over non-motorized transportation modes. Hopefully we learn more about roundabouts through research and not pedestrian and cyclist fatalities.

In my opinion, the roundabout at UBC is a large improvement for slowing down vehicles and severity of collisions, and emissions caused by start and stop traffic. Roundabouts have been in use in Europe and also Hong Kong for a long time. For issues of pedestrian safety, this could be addressed by installing crossing signals, i.e. the flashing amber lights which notifies the motorist to yield. Also in Hong Kong, most roads are fenced off (except for designated crossings, and high medians to discourage jay walking), and includes an fenced island in the middle of the road. Some larger intersections also have pedestrian underpasses and overpasses, and may even include an elevator at both sides of the overpass for people with disabilities. Cyclysts there all know how to navigate a roundabout, and there are even roundabouts that are made only for bicycle traffics. Parking is also discouraged by placing knee to hip-high planter boxes / fences right next to the curb so even if someone parks they will not be able to get out, in which case would allow for better line of sight for both motorists and pedestrians. Roundabouts are great and we need more of them. In places that lack space, a mini-roundabout can also be used, which is just a white painted circle in the middle of the intersection allowing larger trucks and busses to go over them, but to address pedestrian / cyclist safety, education is a key issue along with other components mentioned (over/underpass/elevators/splitter islands/amber signals/bike-only roundabouts to familiarize cyclists without motor vehicle traffic etc…)

At last, I would encourage anyone to explore the road design in Hong Kong through Google Earth, as I do believe they have a very safe and efficient system there.

Roundabouts do not reduce emissions.

When you are wearing trousers, if you gain weight, then eventually the trousers will pinch your belly. And you may say, “the problem is that my belly is pinched,” and therefore the solution is trivial, “I will buy looser trousers.” Then you are free to gain more weight. Since gaining weight wasn’t actually your original goal, though, and in fact the problem was the weight and not the trousers.

This is literally the same problem with the car. The car makes you fat, angry, and impatient. These are the problems with the car. It also pollutes, in rough proportion to how many times you stop and start, but that’s just an auxiliary effect. If you reduce the number of times you stop and start the car then it will seem more convenient, as one of the downsides will be removed. So you’ll drive it more, and longer distances, which will in turn make you fatter, angrier, and more impatient. The primary ills of the car for the society are increased, and ultimately so are the emissions because people substitute longer drives for shorter ones.

That is to say, the emissions reduction of a roundabout is true only if the traffic patterns do not change in response to the increase in perceived vehicular convenience. However, if you did not expect traffic patterns to change then why would you make an additional investment in infrastructure in the first place?

Go ahead, loosen your belt, it’ll cure your obesity.

– Greg

I haven’t really noticed myself things getting worse for pedestrians and cyclists at that intersection at all. In fact, I think it has gotten better. Existing literature seems to be inconclusive about cyclist and pedestrian safety at roundabouts with all the recommended features like splitter islands and cycletracks.

Contrary to the article, I’ve noticed that most drivers do stop for crossing pedestrians and cyclists at the zebra crossings outside of the roundabouts, especially where splitter islands are in place. I find the average delay to be even shorter than the average wait for a full signal phase change at a regular intersection, especially one with advance left turn lights.

Also, UBC’s 16th Ave consultation report shows that the more consistent traffic flows from a set of two roundabouts on 16th avenue will allow it to be reduced to 2 lanes (1 per direction). I can’t imagine that being bad for pedestrian safety at the new mid-block crossing.

The report can be read here: http://transportation.ubc.ca/files/2012/07/Roundabout-consultation-report-6-Feb-06.pdf

Thanks for your responses.

Many engineers are either ignorant or don’t want to take the risk and blame of something goes wrong. Thus, it seems as if traffic lights are the universal solution for everything. They are not. For example a 4KM stretch of road with 8 light controlled intersections. The road is very busy and for this argument, many cars will stop at least 6 of the 8 lights. Each queue has about 20 cars per red-light cycle. The light takes 45 seconds to change back to green which basically mean will lead to around 45 seconds of idling.

Let’s do the math, where T=time in seconds:

– Tidle = 20 cars * 45 seconds * 6 traffic lights

– Tidle = 5400 seconds

= 90 minutes -OR- 1 hour and 30 minutes of idle time

Many municipalities prohibit idling when parked, and drivers may face penalties. This is a good start, but the majorities are coming from the lights especially during peak hours.

I am in no way against this idea, but it comes down to the way they present it to us by being ignorant and putting in more lights, which make it seem like as if they are a collection agency looking to profit off people.

Vancouver is always boasting to become “The Greenest City”. Roundabouts are one of the first steps towards that, not traffic lights. Roundabouts, from common sense, are greener than lights that suck up power, but the approach the city is taking, seems like they are contradicting themselves and hoping no one notices the big picture.

Sure they are encouraging public transportation and cycling, but our public transport is nowhere nearly as developed as New York or Hong Kong. In HK there are literally a big line-up of mini-busses, they take a few passengers (so there will be room for others to board at the next stop), and another will come. Translink’s monopoly will need to end, and people should compete against them. Our public transit is nowhere near that quality. This is a whole new topic so I’ll stop here.

Continuing on: Engineers have tried their best to synchronize the lights but that doesn’t always work perfectly, for example when a pedestrian wants to cross, pressing the cross-walk button will skew the timing algorithm.

Now the point that Greg is trying to argue, is that if people see the roundabout, they will like them and drive even more because of increased convenience. That is plausible to a certain extent, but there are still many other factors as to why we would want a roundabout as opposed to a conventional intersection, including increased safety, reduced power usage as a whole, as roundabouts do not require electricity to run.

And guess what happens when there is a power failure or PLC (Logic Controller) failure? That’s right: 4-Way Stop, and the nightmare that it causes especially on busy multi-lane roads.

Many commuters perhaps even half or larger-half of road users have a busy life. They need to go to work and back home, do some shopping etc… so a good portion of road-users can now spend less time stuck in traffic and idling, and spend more time with their family or their hobbies. That is enough to make a difference. They will have better MPG and spend less money on gas, especially with the rising prices these days.

At least for me, when I drive in the UK or Hong Kong, I don’t use the car any more than here, just because there are roundabouts there.

Reduction in pollution in the area near the roundabout will be a benefit to those people that are living in that area, plus the environmental benefits will definitely add up when we decrease our power consumption. Being “Power Smart” is a message that has been going around for many years. Government in some places have by-laws such as it is unlawful to operate air conditioning unless the temperature rises above X°c, now they should do something on their part by using less traffic lights. It is especially true for places that generate power off the burning of coal or fossil fuels. Think of the big picture!

Slowing down vehicles at the intersection is better than stopping them. An object in motion will tend to stay in motion until another force is acted upon it.

At a light you brake to stop 50KM/h —> 0KM/H and idle and then go 0KM/h —> 50KM/h

At a roundabout you slow down 50KM/h —> 25KM/h, yield, 25KM/h —> 50KM/h.

Certainly it takes more fuel to accelerate 0-50KM/h than 25-50KM/h, not to mention the wear and tear on your brakes. Then you will need pay to change your brake pads, and demand for brake pads will cause more manufacturing to take place, and use up more fresh water during the manufacturing process.

So at a roundabout, instead of stopping and waiting 20-40 seconds, we would be past that intersection in maybe 10 seconds, using less gas, less stress, high speeds and trying to “beat the red-light” thus lower risk of road-rage, and accidents, which leads to even more government spending in hospital costs and emergency services.

As for pedestrian and cyclist safety, I feel safer crossing at a roundabout than a conventional intersection. I would rather be struck at 20-30km/h than at higher speeds. It cannot be denied that the number of fatalities and casualties has been reduced.

As for right-of-way for pedestrians/cyclist safety, we need to think out of the box to innovate. Currently people are thinking it is Pedestrian / Cyclist Safety – OR – Benefits Motorized Vehicle. We need to shift our thinking and instead of using “OR” we need to use the word “AND” instead.

One solution out there is to add pedestrian signals to the roundabout, and the signal will ONLY change to red if and only if there is someone wanting to cross.

If the situation warrants it have an overpass for pedestrians and bikes. Eliminate the inconvenience by placing an elevator at both sides. An example of this is on Nathan Rd and Argyle St in Kowloon. The overpass has 2 elevators on each side, frequently used by elderly, disabled, and strollers.

People need to be educated about how to use a roundabout properly. Some people have never even heard of a roundabout in Vancouver. When I explained the concept they thought it was very chaotic and would lead to more accidents. I might be interested in doing a survey sometime regarding this topic, as the results would be interesting. Most people do not know of their choices, and we need to get people thinking out of the box, thinking “AND” instead of “OR”. We need to think the big picture and co-relate, even when the comparison to something else doesn’t seem to make sense at first, it does.

We need to present people with options, as most of us have never read through nor touched a traffic engineering manual before nor pay attention to how roads are engineered abroad.

It is just how the human brain works. If someone sees something that they have never seen before, the brain will try to understand and wiring different thoughts together, and re-enforcing what it wants to believe, not what is correct.

If roundabouts work elsewhere in the world like in the UK, it should work here, because I don’t believe people here are in any way less capable than those abroad. They won’t be building any more of them otherwise.

In fact in the US, a bill has been passed that mandates roundabouts to be considered first in the construction of any new roadways containing intersections.

Statistics have also shown that people that strongly oppose a roundabout, later change their minds and admit they were wrong, and instead embrace the new concept.

Take a look at the video on YouTube “Glen Falls Residents Love Roundabout”.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dHnY8IGv1sY

Vancouver is a big city, and I don’t buy the fact that not a single arterial street would work with a roundabout. People will accept it when more gets built, but that needs to happen first.

What I mentioned above is just a nutshell in traffic engineering. There are numerous studies out there already; some are done right in BC addressing safety, pollution, quality of service. Take a look at the one done at UBC regarding the 16th Avenue roundabout. Another one has been released recently called “Automated Roundabout Safety Analysis” by UBC.

People are skeptical because it is something new. I remember people saying that they are scared to take the Skytrain when it first opened back during Expo Vancouver. They were worried about what would happen if the computer crashes, because there is no driver, and said “Let’s wait and see first, because I don’t want to be a lab rat.” It’s just human nature.

Know your facts, know your options, do your research, and consider giving this a chance.

I think for cyclists this intersection is really quite dangerous. A cyclist has two choices to cross: either go with traffic or go with the pedestrians.

Going with traffic is tricky, as this is a two-lane “turbo” roundabout, requiring you to change lanes in order to turn left or go straight. With motorists going 50km/h and more, that lane change can be very tricky to effect.

But going with the pedestrians is problematic as well: most motorists are looking for pedestrians going at walking speed towards the crosswalks (if they are looking at all), so if you go at even a relatively slow cycling speed, you have a high chance of getting hit. But a lot of motorists do not stop for users of the crosswalk, so in practice to make a left turn you have to make four lane crossings at slow speed.

As for pedestrians, the fact that they built this right next to a school is particularly aggravating. From what I’ve heard, the current advice for the walking to school campaign being run at that school is for kids to find somewhere else to cross the road. Except … I don’t believe there are any other crosswalks within half a kilometre.

Sadly, Campus and Community Planning seem to think roundabouts are the best thing since sliced bread.

In regard to your comment:

“n England, where roundabouts are commonplace, drivers are reasonably vigilant and yield to pedestrians”.

As a pedestrian and driver in England I think that an important factor is that in the UK there is no Jaywalking law, and pedestrians always have priority on roads where they are permitted – which is everything except Motorways, a few dual carriageways and many tunnels and flyovers (elevated sections). A car hitting a pedestrian is almost always liable, needing to prove that it was impossible to avoid the collision.

This makes it quite easy to cross at roundabouts. Of curse if there are sufficient gaps in the traffic to cross without cars having to slow then you should wait, but otherwise if you look for someone who can stop, make a friendly wave, and step out then you can be almost certain they will do – though you should always be prepared to step back if they don’t see you!

Here is an article about Brits getting in trouble for using this method of crossing abroad! http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/6251431.stm

In Saskatoon a “neighbourhood” roundabout was installed on my daily walking route to replace a 2-way stop. After a few months I decided that even though the vehicle counts were low, quite a few of the motorists I encountered at the roundabout posed a danger to me. My solution was to alter my route to avoid the roundabout.

I found a reference on the on the US Federal Highways Administration site to a study, NCHRP-572 {http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_572.pdf}. The report indicates that observations measured 32% of the vehicle failing to yield pedestrian right of way at a roundabout compared to only 4% at 4-way stops {page 87 Table 63 Motorist behaviors by traffic control type}. In the same document it states that 14% of the crossings resulted in the pedestrian running. {Page 86 Table 61. Pedestrian behavior at roundabout crosswalks}. The same report reviewed accident reports and noted the accident numbers at roundabouts are low.

With these facts in hand, the report concluded roundabouts are safe for pedestrians. I on the other hand concluded that roundabouts are viewed by pedestrians as a high risk, unpredictable intersection and extra attentiveness is paid when using the crosswalks. If motor vehicles are not yielding right of way 32% of the time, I have to believe that terrified pedestrians deserve credit for accident avoidance.

Why would anyone would use these traffic devices when pedestrian crosswalks are required?

It might take time. Drivers need to get more used to having non traffic signal controlled crossings. Also, the North American design isn’t the best they could use to make it safer. The Dutch design for the car lane approaches decreases the speed and requires the driver to make conscious decisions, and there is slower speed. The speed on the approaches themselves is more likely to be 30 km/h. You can also add a raised table to the pedestrian crossing. The pedestrian crossing can be marked with zebra stripes rather than the smaller parallel line type, which in the Netherlands you might indeed mistake it for a crossing where pedestrians don’t have priority.

And the Dutch don’t built multi lane roundabouts where pedestrians expect to cross. Well, there are a few stranglers from a long time ago, but these days if you need to cross more than one lane at once, your roundabout is too big and it needs to be grade separated from pedestrians, and there is usually a median between the two directions as well. The distance from the pedestrian crossing (well, generally, bicycle crossing, but if for some reason that is not provided, the pedestrian crossing) to the roundabout right edge is about 10 metres not 5 or 6. More space for drivers to deal with the same number of actions at a time and space for even buses to yield correctly, although 12 metres would make the most sense for that here.

Roundabouts are the worst. They are accidents waiting to happen. Just stray with the four way insection. More accidents happen in roundabouts but less major accidents. But a four way stop has less accidents, but more major accidents. They could prevent more accidents but installing low wattage cell phone blockers in vehicles, while driving and they would be disabled when vehicles are turn off. If you don’t like this idea, it is in the near future so get use to it. Mean while don’t use your phone while driving and save someone’s life.